Stefan Shaffer shares the latest US Private Capital Report for April 2023. Private market liquidity conditions currently are among the most arduous in the last decade. The recent crises surrounding SVB/Signature/FRB/CS only serve to exacerbate already bearish credit markets rocked by high interest rates (SOFR at ~4.85%), stubborn inflationary influences, and continued macroeconomic weakness. Read the full report below.

The Private Capital Markets are a “Ball of Confusion”

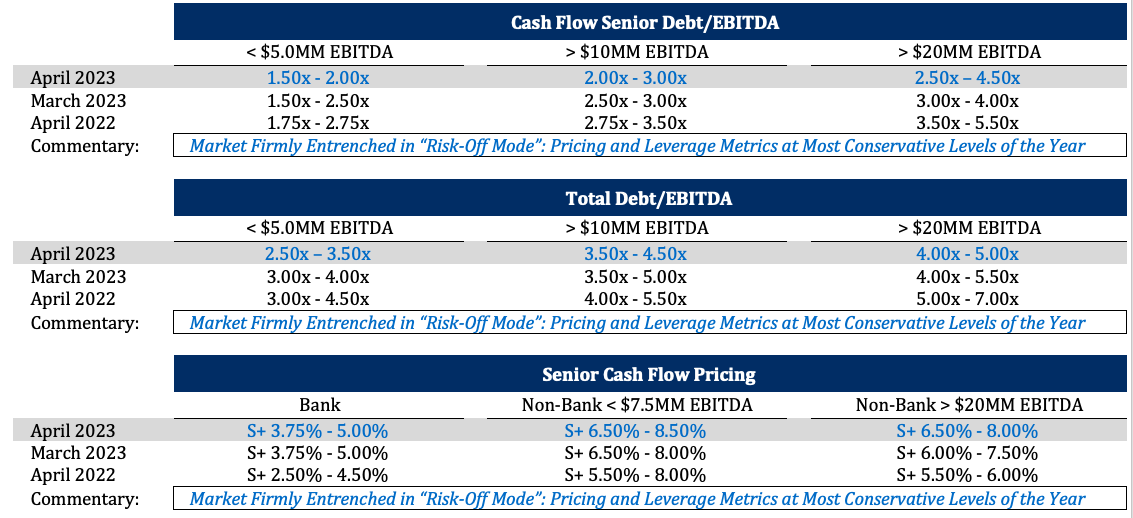

We are modifying our leverage and pricing metrics across the board in April, lowering leverage multiples by approximately a half-turn of EBITDA and increasing credit spreads by a factor of 50-100 basis points. The modifications are not representative of a wholesale re-pricing of risk in the private capital markets per se, but rather an expression of the increased vulnerability of the market to extraneous events, most vividly exemplified by the recent tribulations of SVB/Signature/FRB and CS. More simply stated, the current private capital markets are a “Ball of Confusion.”

Before getting into the most recent round of volatility, it is important to acknowledge the fragility of the private capital markets going into 2023. In January of this year, Bankrate published its Fourth Quarter (of ’22) Economic Indicator Poll. The poll noted that the “U.S. economy has a 64 percent chance of contracting in 2023, according to the average forecast among economists.” The Conference Board’s US Recession Probability went further and registered a 99% probability of a recession in 2023. Earlier in the year, recession fears were fueled predominantly by repeated Fed interest rate hikes; the Fed Funds rate had jumped from ~.08% in January 2022 to ~4.33% in January 2023. Entering April, the Fed Funds rate sits at ~4.57%, and SOFR is ~4.85%.

On March 10th of this year, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failed after a bank run, marking the second-largest bank failure in United States history and the largest since the 2007–2008 financial crisis. It was one of three March 2023 US bank failures (including Signature and First Republic Bank). While the Fed, Treasury, and a consortium of major money center banks effectively stemmed the contagion from a more systemic collapse in the U.S. banking system, the March crisis exacerbated an already shaky private market. Goldman Sachs raised its U.S. recession probability from 25% to 35%, while the broader Bloomberg Forecaster Consensus for U.S. Recession Probability Median Forecast registered a more sobering 60% following the March banking scare.

The reverberations continue today. The chief economist at Apollo, Torsten Slok, explained that he; “estimated that the recent disruptions have produced tightening equivalent to the Fed raising interest rates 1.5 percentage points, twice the size of the biggest single increase by the Fed last year,” while economists at Goldman Sachs noted that because lending conditions had already begun to tighten “due to widespread recession fears,” the recent stress in the banking sector was equivalent to a quarter or half-point increase in rates. The economists added that “the risks are tilted toward a larger effect,” and “raised the likelihood of a recession in the next 12 months.” JP Morgan Chase Chief Executive Jamie Dimon was a little more positive in his annual letter to shareholders in early April, writing that “jitters would clearly cause some tightening of financial conditions as banks and other lenders become more conservative. Although stricter lending practices may have the same dampening effect on the economy as higher interest rates, for now the economy is in pretty good” shape.”

While credit conditions will be impacted for issuers of all sizes, the impact on lower middle market issuers will be markedly more profound. Smaller companies (i.e., sub $15 million LTM EBITDA) do not have access to the larger traded public, 144A, and syndicated markets and rely primarily on local and regional commercial banking institutions, the same banks most adversely affected by the March banking crisis. Today, smaller banks (i.e., <$250 billion in assets) account for ~49% of all commercial and industrial (“C&I”) loans. These regional institutions face a four-pronged threat: (i) increased Fed oversight; (ii) decreased depositary bases; (iii) enhanced shareholder pressure; and (iv) increased costs, which collectively may result in a wholescale restructuring of their balance sheets and ultimately a more pronounced contraction in credit availability. In short, smaller banks will almost inevitably make a deliberate and prolonged retreat from bank credit growth, making borrowing more difficult and decreasing liquidity for middle market issuers. While larger middle market issuers (>$15 million in LTM EBITDA) will still have access to the non-bank direct lending community, the cost of capital with this lending constituency will start at SOFR +7.5%, translating to ~12.4% floating (vs. SOFR +4.00% or ~7.80% for comparable commercial bank pricing). In addition to higher floating rates, the non-bank lending community also comes with higher closing fees (~2.00% vs. 0.50%-1.00% with a commercial bank) and prepayment penalties (~103 in year one and declining thereafter vs. a par call with a commercial bank).

While credit conditions will be impacted for issuers of all sizes, the impact on lower middle market issuers will be markedly more profound. Smaller companies (i.e., sub $15 million LTM EBITDA) do not have access to the larger traded public, 144A, and syndicated markets and rely primarily on local and regional commercial banking institutions, the same banks most adversely affected by the March banking crisis. Today, smaller banks (i.e., <$250 billion in assets) account for ~49% of all commercial and industrial (“C&I”) loans. These regional institutions face a four-pronged threat: (i) increased Fed oversight; (ii) decreased depositary bases; (iii) enhanced shareholder pressure; and (iv) increased costs, which collectively may result in a wholescale restructuring of their balance sheets and ultimately a more pronounced contraction in credit availability. In short, smaller banks will almost inevitably make a deliberate and prolonged retreat from bank credit growth, making borrowing more difficult and decreasing liquidity for middle market issuers. While larger middle market issuers (>$15 million in LTM EBITDA) will still have access to the non-bank direct lending community, the cost of capital with this lending constituency will start at SOFR +7.5%, translating to ~12.4% floating (vs. SOFR +4.00% or ~7.80% for comparable commercial bank pricing). In addition to higher floating rates, the non-bank lending community also comes with higher closing fees (~2.00% vs. 0.50%-1.00% with a commercial bank) and prepayment penalties (~103 in year one and declining thereafter vs. a par call with a commercial bank).

Issuers with less than $10 million of EBITDA generally do not have access to the non-bank lending community and may have to supplement their term loan needs with traditional mezzanine-focused lending groups such as Small Business Investment Companies (SBICs), where pricing tends to be a fixed rate (ranging from 12% to 14+%) and may include potential warrant dilution. Closing fees and prepayment penalties will be similar in magnitude and scope to those charged by the non-bank lending institutions noted above.

The negative implications for middle market issuers resulting from a contracting commercial banking sector range from inconvenient to downright draconian. For instance, discretionary capital expenditures will almost certainly be curtailed. According to Pantheon Macroeconomics, the projected decline in capex plans is already “alarming.” The National Federation of Independent Business (“NFIB”) percentage of firms planning to raise capex in the next six months is down over 80%. From a credit quality perspective, middle market issuers, as a general proposition, already have interest charge coverage ratios substantially below the broader market of corporate issuers. Increases in capital costs will only tighten coverage ratios and potentially risk increased default rates. Finally, middle market issuers tend to have distinctly shorter debt maturities, thus facing a noticeably steeper maturity wall than their larger corporate brethren. Increasing the overall cost of capital for middle market issuers, especially lower middle market issuers, could prove to be nothing short of existential.

A true Ball of Confusion.

Tone of the Market

Private market liquidity conditions currently are among the most arduous in the last decade. The recent crises surrounding SVB/Signature/FRB/CS only serve to exacerbate already bearish credit markets rocked by high interest rates (SOFR at ~4.85%), stubborn inflationary influences, and continued macroeconomic weakness. As a general proposition, commercial banks, especially smaller regional institutions, are under pressure (by the Fed, shareholders, and depositors). Not surprisingly, credit committees are taking a pronounced step back. From a quantitative perspective, that translates to approximately a half-turn of EBITDA of less leverage, and ~50bps higher spreads. From a qualitative perspective, that means an increased bias against cyclical or storied credits, thinly capitalized structures, and debt recapitalizations. Historically, commercial bank sponsor coverage groups provided more aggressive lending metrics compared to their non-sponsor peers; however, that differential seems to have dissipated. The retrenchment of the commercial banks provides cover for the non-bank direct lenders to be less aggressive, resulting in tighter leverage metrics and higher pricing across the board. It should be noted that there is currently no dearth of liquidity in the non-bank market, but it is a decidedly more selective market.

Minimum Equity Contribution

Cash equity contributions have become the primary focus point for all leveraged buyouts in the private market. Almost regardless of the enterprise multiple, lenders are focused on a minimum 50% LTV (i.e., equity capitalization of 50%). More importantly, actual new cash in a deal should also constitute at least 75% of the aggregate equity account. For the foreseeable future, the days of 20%-25% equity contribution are over. While lenders will certainly give credit to seller notes and rollover equity, the new cash equity quantum is the primary metric.

Equity Investment and Co-Investment

Liquidity for both direct equity investments and co-investments continues to be robust in the new year, and in many cases, more competitive debt terms can be achieved where there is an opportunity for equity co-investment. Interest in independently sponsored deals continues to be strong as well, but investors will require that the independent sponsor has real skin in the game (i.e., a significant investment of their own above and beyond a roll-over of deal fees). Family offices remain the best source of straight common equity, and, continuing the trend established in 2020, credit opportunity funds, insurance companies, BDCs, and SBICs will actively pursue providing both debt and equity tranches.

Stefan Shaffer

Managing Partner and Principal

Stefan has over 30 years of experience in the private market includes hundreds of transactions in North America, Asia and Europe. Prior to becoming a principal at SPP Capital, Stefan was a Vice President in the Private Placement Group at Bankers Trust Company where he was responsible for origination, structuring and pricing of private placements for the Capital Markets Group, both nationally and internationally.

[email protected]

Ph: +1 212 455 4502